10 STEPS TO COMMUNITY REINVESTMENT

The Interagency Working Group on Coal and Power Plant Communities and Economic Revitalization (Energy Communities IWG) will promote job-creating investments in communities already impacted by coal mine and power plant closures and will also be proactive, investing now in the communities likely to be impacted by additional, near-term declines in coal production and generation from coal-fired power plants.

This is a step-by-step guide intended to help communities and workers start the process of planning or responding to economic and social changes resulting from the energy transition or any major economic shift. It is a planning and action tool for community leaders, volunteers, and change agents. It’s also a guide to help communities and other eligible entities access federal funds to address economic resiliency.

The guide has 10 steps, divided into the categories of Planning, Executing, and Managing. It’s designed to be applicable to any stage of economic transition. Start with the step that best fits your current needs or stage of a specific project. Remember, economic change is an iterative process. Things may not always develop according to these steps. Flexibility, regrouping, or moving back to a previous step may be necessary.

The guide includes questions to ask internally or outside the community that raise issues to consider, as well as examples illustrating each step. Also included are several guides that federal agencies, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), and philanthropies have created as guidance for their work, such as energy installations or brownfield redevelopment, some of which may be useful for your community and are linked as resources here.

BEST PRACTICE #1: START EARLY! IT’S NEVER TOO EARLY TO PLAN FOR CHANGE.

Sustainable, positive change takes leadership, planning, funding, and ongoing support to implement transition. These actions are addressed in the guide and throughout the website.

The impacts of change have likely been percolating for a long time and have been influenced by other aspects of the economy, apart from energy issues. Needs are wide and varied and will be articulated differently, depending on where you sit, how you have been impacted, regional history, and the perceived future. If you’re new to this effort, motivated to take action, or just want to raise your hand with a question, it’s time to get started. This guide is organized so you can pick up at any stage of your transition efforts.

This guide is also an introduction to using the Energy Communities IWG’s clearinghouse of federal funds, directed toward the needs of communities facing an energy transition. Importantly, it is intended to strengthen and shore up communities so they can face transitions head-on and thrive economically and socially.

There are funding opportunities in the clearinghouse that address social and economic issues such as support for housing, workforce training, health care, economic development, transportation, broadband, and just about everything a community may need to have a healthy economy and meaningful work for its residents. While federal funds may be able to resource your concept or project, other entities such as states, philanthropy, Community Development Financial Institutions (CDFIs), and the private sector may also be important sources of capital and support. Start here at our funding page and visit this instructional video on how to navigate the clearinghouse.

On the technical assistance page you'll see that the ongoing support has been divided into three buckets:

- The first is applying for technical assistance funding. These are competitive grant funds to, in most cases, hire consultants to help plan, write, implement, or manage a project or process.

- The second bucket is “services." These options are ways you can get help at no cost from a specialist. Most require some type of simple application, but many also have contact information for you to learn more about the funds in an agency, eligibility, timing, or other types of assistance.

- The third bucket is a list of static resources, webpages, webinars, case studies, and written commentary, divided by agency, and includes a point of contact for each agency.

For more information, visit the technical assistance page or watch our demonstration video on technical assistance resources.

BEST PRACTICE #2: TAKE THE TIME TO LEARN ABOUT THE HELP THAT IS AVAILABLE. IT WILL SAVE TIME AND MAKE THE WHOLE PROCESS EASIER.

Identify Your Needs

Your community and region may be facing a transition that wasn’t anticipated in the traditional community plans, or a future that members of your community did not anticipate for themselves and their families. This requires new thinking to face impending change.

BEST PRACTICE #3: CLEARLY DEFINE WHAT YOU ARE TRYING TO ACHIEVE.

A clearly defined problem is more likely to result in meaningful solutions. Take the time and effort to articulate your needs and goals. What are you losing with this change? What do you hope to preserve or gain? What else would help or hinder this from happening? What does the best-case scenario look like? In a later step in the guide, you’ll need to outline a strategy to achieve those goals, so try to be specific.

Many communities have a Comprehensive Economic Development Strategy (CEDS), a Master Plan, an Economic Development Plan, or another type of planning document that identifies the land use and economic development needs in the community. These can be used as starting points for identifying goals and potential federal funding options. If your plans are dated or weren’t written to address the challenges you now face, this is the first goal: Bring the community and the workers impacted together to state the problem, as they see it, from the first row, and rethink the goals and the new future the community faces.

BEST PRACTICE #4: ENGAGE THE COMMUNITY. THIS IS THEIR PLAN AND THEY NEED TO PARTICIPATE AND SUPPORT THE CHANGES. EVERYBODY WINS.

Community engagement is necessary to achieve a shared vision that will be supported over time. Ensure that workers and the community stakeholders have a chance to be part of each step and have a seat at the table in some form. There are many examples of community engagement at various levels of depth and investment.

Step 2 in this process is forming a team to lead and sustain the effort. You may have already had to form a team to achieve Step 1—Identifying your goals. Don’t worry about which comes first. Just do it and recognize that goals may need to be revised as new information arises and priorities change.

Community consensus on how to survive and thrive during a fundamental change that was either unexpected or unwelcome, or both, is essential. Plans and actions are more likely to be successful if you can remind those who disagree with them when they see action that (1) this is the will of the community (reference the goals) and (2) this work is for the common good.

A note of caution: Change can resemble or result in grief and needs to be treated as such. Honor the past, respect that each person is impacted in a different way, and be patient with how trauma can be displayed. You may see anger, blame, and denial, but it’s not directed at the process; it’s directed at the fact that there is irreversible change. Keep on the path. Engage those who disagree in helping to form the future of the community. Change takes time, and benefits may have long payoffs, but people want to see solutions now. No approach or solution will be universally accepted.

Identifying Goals

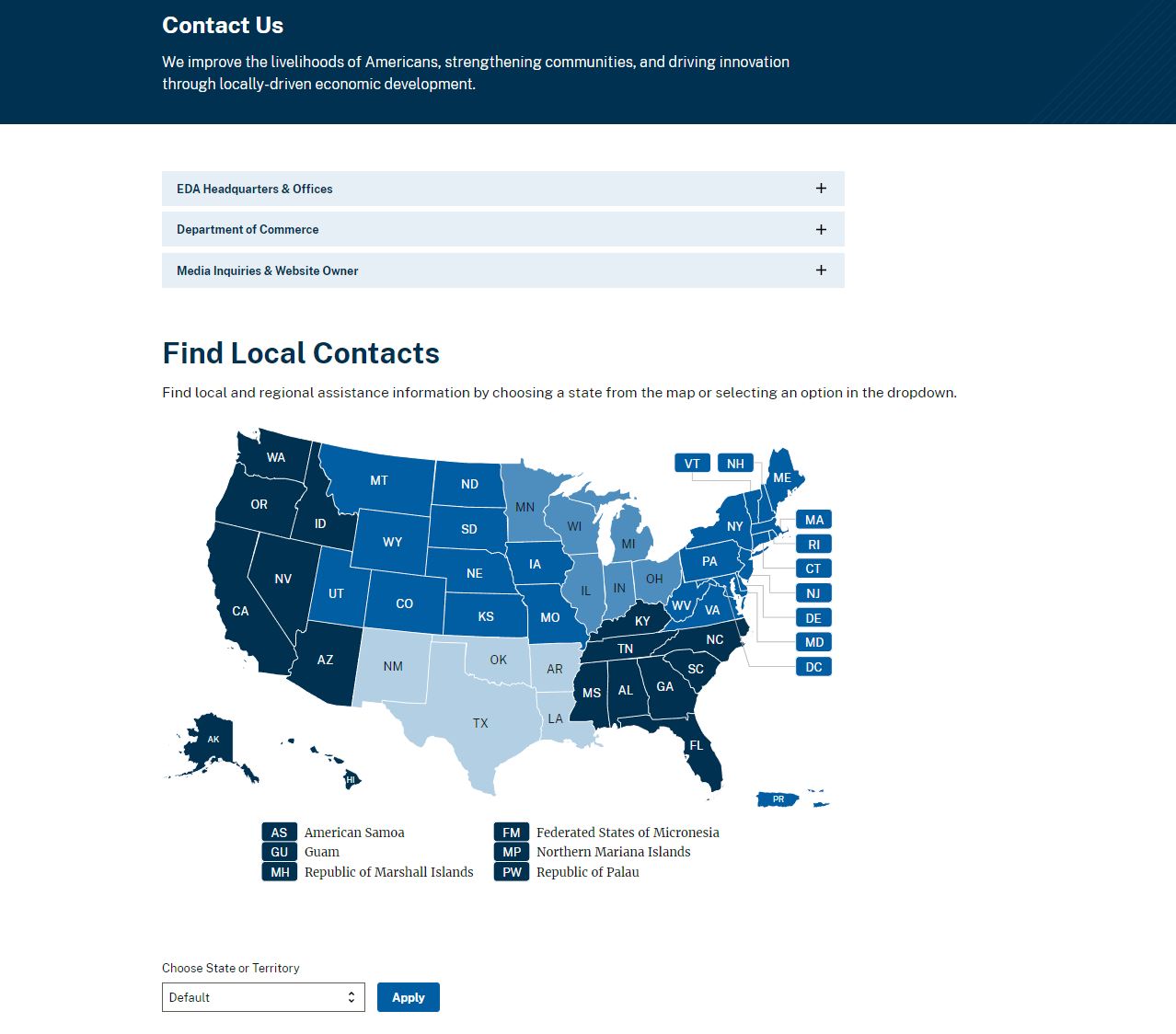

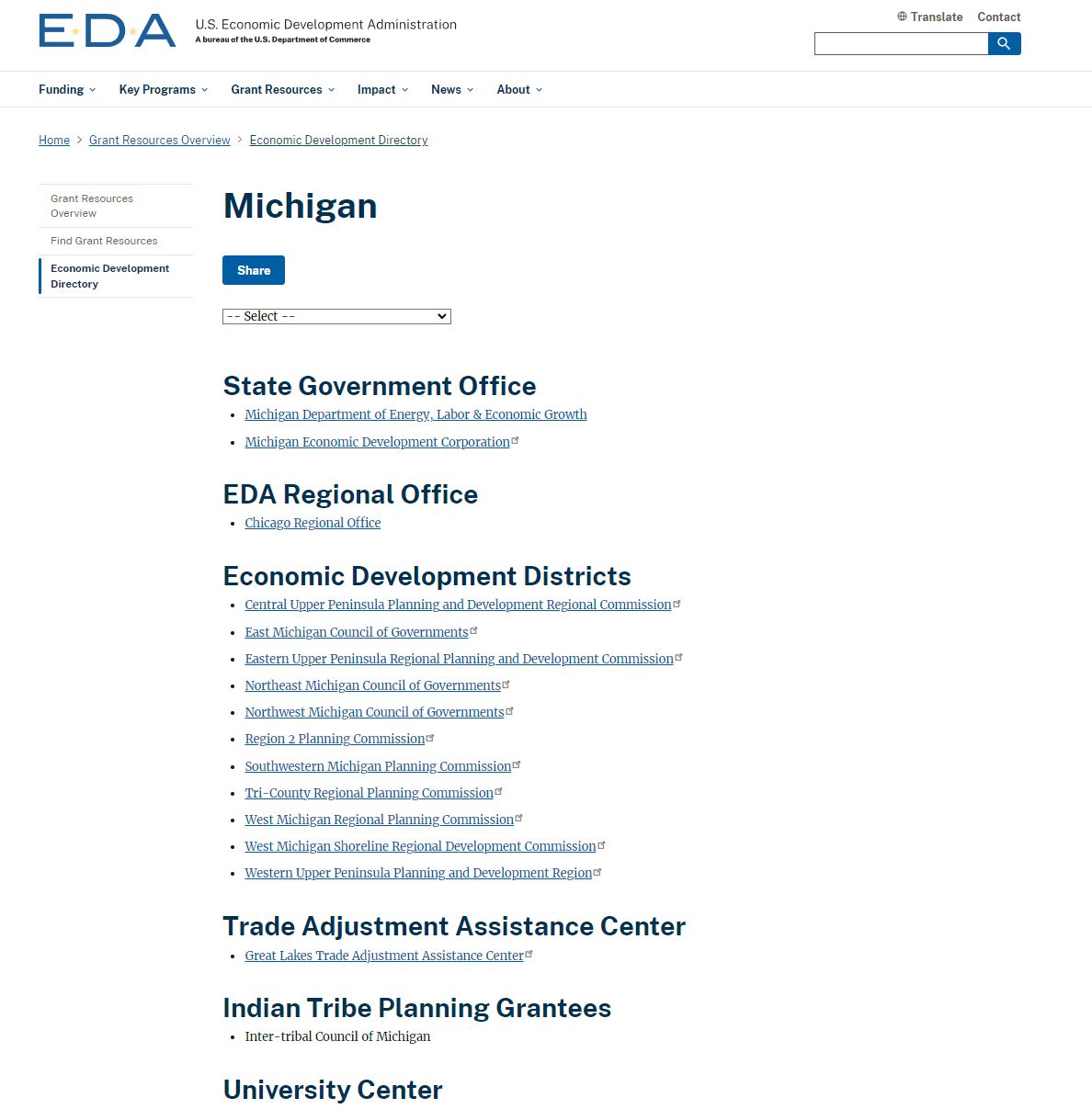

Every state has one through the U.S. Economic Development Administration (EDA), but there may not be any local or regional professionals.

Collect the plans in the region and community that are relevant and completed within the last 10 years. Synthesize the goals and tasks sections to create a starting point.

If there is time, visit local service organizations or other local community champions to discuss the issues and current goals, solicit support, and gather ideas about what will be necessary to update your goals. Be sure workers are represented throughout the process.

Identify decision makers in the community. Meet with them to discuss the issues and current goals, to understand previous efforts and constraints, and to solicit support.

BEST PRACTICE #5: DON’T REINVENT THE WHEEL – USE EXISTING PLANS, LANGUAGE, AND RESEARCH WHERE APPLICABLE.

Associated Resources

Listed below are examples of how other agencies and groups get started planning for transition.

This is an example of a goal-setting worksheet focusing on port development. It illustrates how to assess the primary concerns and determine goal-setting strategies.

This process is an example of a community building on past successes that offers low-income, minority, tribal, and overburdened communities methods to shape development that respond to their needs and reflect their values. See this page on Community Engagement.

This step-by-step guide and worksheet is focused specifically on energy transition and is directed at communities with full-time staff and resources.

Form a Team

Identify Your Needs

Transforming a local economy is complex and impacts the entire community. Building a team of government decision makers, trusted leaders, workers, and community champions to collaboratively envision and pursue this transformation is a critical first step.

The Aspen Institute’s definition of community capacity is “the combined influence of a community’s commitment, resources and skills that can be deployed to build on community strengths and address community problems and opportunities.” Building community capacity also means bringing together the skills and commitment to develop and leverage resources and power to make something happen. Communities approach transition at various levels of capacity and your team, which will evolve as the process unfolds, needs to reflect this.

The purpose of Step 2 is to find people and organizations that will be able to find solutions and a path forward to address the goals outlined in Step 1. The strategy to address goals will be developed in Step 3.

BEST PRACTICE #6: DON’T PLAN WHILE LOOKING IN A MIRROR. ENGAGE PEOPLE WITH DIFFERENT BACKGROUNDS, CULTURES, AND EXPERTISE.

Who to Include on Your Team

Your team doesn’t have to do all the work. Bring in experts and interested people along the way as needed. (See Best Practice #5) People are more willing to participate when there is a defined role and time commitment. Respect that people may have skills or expertise they are willing to share but may choose not to sit on a committee or participate in a public meeting. For most people this will not be their day job and they are volunteering their limited time in what may be a contentious atmosphere.

Steps to Consider When Forming a Team

| 1 | Identify government decision makers. Key government officials are the mayor, county board chair, administrative leader, assessor, treasurer, and planner. They may be known with other titles in different parts of the country. Identify trusted leaders and champions. | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | Publicize the transition planning and implementation process that is taking place on community websites and at public meetings and offer ways to be involved or stay informed. | ||

| 3 | Take action to ensure groups that are often underrepresented are made aware of the process, such as seniors, minorities, non-English speakers, and seasonal populations. | ||

| 4 | When the team is formed, define roles and rules of procedure. This means appointing a chairperson, determining how decisions are made – consensus or majority, for instance – and establishing meeting conduct, such as using Robert’s Rules, so everyone can understand and participate. | ||

BEST PRACTICE #7: WORK WITH DECISION MAKERS, WHOMEVER THEY ARE. YOU NEED THEM.

Government decision makers are elected or appointed officials who control and/or influence the use of public funds, land use, and publicly funded services such as schools and recreation. Generally, community plans are those adopted by the local government or economic development agency. These are the people who manage government grants and tax dollars.

Trusted leaders take all forms and are frequently the volunteer leaders in community foundations, service clubs, religious organizations, Community Development Finance Institutions, or school boards. They are also leaders of nonprofits and philanthropic organizations. They are invested in the wellbeing of the community and demonstrate this by their willingness to lead or invest their institution in an effort. People respect them and their opinions and they can have great influence in difficult times.

Community champions are people who may also be trusted leaders but have a passion for something in the community and will devote effort and leadership to achieve it. They can be coaches, teachers, or retired or working professionals; they can be the person who wants to ensure there are holiday decorations downtown, better accessibility at the fishing dock, or an oral history of the community. These people are invested in the community and can bring support and energy to positive change.

Workers are essential to the team. These are the people who have worked or supported the energy field, keep the water system running, are unionized/non-unionized, and may be losing their livelihood with the energy transition. Workers are an example of a stakeholder who knows the challenges of working in industry and may be directly impacted.

Associated Resources

Below are some examples of approaches to building a team, eliciting public involvement, and building coalitions and power. These are detailed examples from various fields that may have components applicable to your community.

This is an example from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s port development process. It discusses the importance of developing relationships with various groups and the regional nature of potential solutions.

This National Institute of Health guide uses environmental health examples to discuss the components of capacity building with examples of organizations and the skills they offer that can be helpful in this step.

This Prevention Institute document explains how to build effective coalitions, as opposed to competing agendas among groups, and how these coalitions can move a community toward their goals versus becoming stagnate in local dissention. The guide uses preventative health issues as an example.

Develop a Strategy

Now that you’ve identified projects or needs in your community and formed a team of stakeholders who are going to work on this effort, the next step is developing a strategy. Which investments will have the greatest impact? How do you access those investments?

The strategy needs to reflect the consensus of the community so that when put into action, there is support and commitment to make it happen. Change is hard and the more the strategy is directed and implemented so the impacts are addressed, the greater chance it will achieve its goals and be successful.

The strategy will also depend on a community’s strengths, weaknesses, and opportunities. These may be described in the locally generated Comprehensive Economic Development Strategy (CEDS) from your Economic Development District (EDD), noted in Step 1. One of the resources listed here calls this “identifying the levers of change.”

Engage the Community

Engaging the community takes thought and effort. Stakeholders come from all walks of life and potentially several geographies in your community. Identify ways to hear these voices. Hold public meetings with your leadership team and the public at various times of day, in locations open to everyone, such as libraries, religious institutions, or schools, and take advantage of existing networks, such as service clubs, neighborhood organizations, labor unions and other worker organizations, senior centers, and regular government meetings. (See Best Practice #4)

Authentic engagement includes accommodating people who require translation services, the hearing impaired, those with various physical abilities, and those who work various shifts. Ideally, all demographics should be represented. The location and opportunities to speak are important, as is the follow-up from the meeting with publicly available notes, next steps, and ways to stay engaged.

Set Goals

Goals state the destination. Strategies are the map to that destination. It’s imperative to know where you are going in order to find out how to get there – and that’s the importance of goals. There is a plethora of material on how to write goals, measure success, and establish the strategies and tasks to get there. In this step, you are stating your goals in the most concrete way possible. (See Best Practice #3)

The following worksheet shows one example of meaningful goal-setting, known as the Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, and Time-Bound (SMART) system.1

| The Goal Should Be | Question to Ask | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Specific | What needs to happen? | Upgrade the drinking water supply to serve the entire community and undeveloped land within the municipal boundaries. |

| Measurable | How will success be measured? | Success is upgrading the entire drinking water supply. Partial success is upgrading a portion of the supply. |

| Achievable | Is this project possible? | The water supply improvements can happen with a low interest loan from USDA-RD. Need to know if the thresholds of income and subscription will be met. |

| Relevant | Is this goal fundamental and necessary to help the community transition and diversify their economy? | Water supply upgrades are integral to maintaining and attracting residents and businesses. A lack of upgrades will jeopardize water quality and distribution. |

| Time Bound | How long will it take? | The project will be completed prior to the plant closure in year _____. |

Suggestions to Help Set Strategy

- Gather the facts (See Step 5)

- Demographic trends

- School enrollment

- Vacancy rates

- Land use changes

- Employment

- Tax base impacted, collection cycle, etc.

- Land occupied/controlled by utility

- Anything else that is being impacted by your energy transition or is expected to be impacted

- Gather opinions – There is extensive community and stakeholder input during this step. Articulate local concerns, desires, and needs. Identify items where there is consensus.

- Gather the facts (See Step 5)

- List the options that have been discussed in Steps 1-3.

- Quantify the need – The water system currently is undersized by X as evidenced by the inability to site additional development, to meet insurance requirements, or to meet flow demand.

- Quantify the solutions – For instance, the size of the water system needed, the cost to construct, the ability to pay, the potential sources of cost share, if required.

- Quantify the limitations – Cost-share limitations, inability to fund up-front costs such as engineering, lack of grant writing capability.

- Prioritize the solutions so there is a starting point. Map tasks in order of importance and dependence on each other.

- Identify early and/or easy wins to spark momentum.

- Set a timeline to work on each potential solution.

Associated Resources

Successful public involvement adds credibility and sustainability to decisions that are made. If your community is facing a controversial decision, or looking for input from groups who historically do not engage, this guide from the U.S. Department of Transportation will provide strategies to engage the public in a meaningful and interactive way, using transportation as a backdrop.

This U.S. Environmental Protection Agency guide helps to identify some of the best practices for planning, and skills and behaviors that government agencies can use to design and implement a meaningful public participation program.

This is an example of a more sophisticated process focused on energy transition in a community. The ideas presented in this U.S. Department of Energy playbook are useful as you proceed through creating a strategy.

This Just Transition Fund document discusses creating and measuring goals as well as the importance of stakeholder engagement. This blueprint takes a deeper dive into the importance and thinking behind establishing and measuring goals.

Make a Plan

Now you have a strategy. Developing an actionable plan to implement that strategy comes next. The purpose of a plan, which is an extension of your strategy, is to create the story about your transition needs and work. This work can be used as the narrative and the justification for a potential grant application.

BEST PRACTICE #8: KEEP IT SIMPLE, IF YOU CAN.

Starting with the goals in Step 3, develop a list of needs, a timeline, those responsible, experts, other resources needed, and a method for measuring the success of the project. Charts can make this an easier process.

A plan is also important because it will be required if you apply for public funds and possibly private funds. Federal funding agencies will want to hear about your plan, that it is consistent with the community’s overall planned future and desires, and that there is a strategy for carrying out the plan. The time and energy spent writing not only helps to add clarity to the community’s goals and strategy and what comes next and why, but it can be reused at multiple points in the funding process. Federal agencies and nonfederal sources of funds need to see that the community has thought through the funding request.

| Category | Implementation Strategy | Group Responsible | Priority |

|---|---|---|---|

| Revise the Zoning Ordinance |

|

Township Board; Planning Commission | Immediate in Master Plan and Zoning Ordinance |

| Educate Township Residents |

|

Township Board | Immediate |

| Research Water and Sewer Expansion in the Township |

|

Township Board; Planning Commission; Municipal Sewer and Water Providers; USDA; Professional Engineers | Immediate |

A plan does not have to be long or complicated. It does, however, have to be a public document, adopted by the governing body of the community. Often an existing community Master Plan, a Comprehensive Development Plan, or a Capital Improvement Plan can be amended to include transition plans, depending on the nature of the plan. However, these types of plans can be complicated and time-consuming to amend. A simpler approach can be writing a plan that takes the form of a resolution, an annotated set of statements by the governing body, or as a simple separate stand-alone document.

Many small municipalities and rural areas do not have staff for this work, so be sure to solicit and accept help from others (e.g., capable volunteers [most communities have them – See Step 2], local colleges, philanthropy, and volunteers who can put the public input, goals, and strategy into words).

Associated Resources

These are some examples of approaches to building a team, eliciting public involvement, and building coalitions and power. Listed below are examples of how other agencies and groups get started planning for transition.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency uses an action plan, outlining a set of activities for a project, and designates timing and leads for each activity. The plan also considers the engagement strategy that will support your project best and define how you plan to measure success.

This U.S. Environmental Protection Agency template can help with creating a simple community action plan. The template can be augmented with the text necessary to explain the purpose, the process for choosing this plan, and how it will impact the community upon completion.

This example of a simple community action guide from Community Tool Box, describes “the overall goal of action planning is to increase your community’s ability to work together to affect conditions and outcomes that matter to its residents—and to do so both over time and across issues of interest.”

You can find examples of nonprofits and communities who have written and executed portions of their plan in the grantee section of this website.

Get the Data

Often this step needs to happen concurrently with setting goals and strategies. As with all steps in this guide, the steps are meant to be used as needed to achieve funding, implementation, and success. Data gathering, analysis, and use usually spawns more questions in the planning process, making this step an iterative process.

BEST PRACTICE #9: PROVE YOU NEED WHAT YOU ARE ASKING FOR. SUPPORT EVERY STATEMENT IN YOUR GRANT WITH DATA, EITHER FROM FACTS OR CONSENSUS OPINIONS.

Showing the need for and the benefits of meeting your community’s needs in your plan is essential to a successful grant application. It’s important to make a strong case with data that supports your request (needs statement), as well as the uses of funds (proposed projects or solutions). This may be showing financially based needs, lack of services, insufficient workforce or services to support the workforce, or inadequate infrastructure. The use of the funds you are applying for, federal or otherwise, must demonstrate, and to some extent prove, the solution with measures of success. Remember, the measures of success are stated in your goals in Step 3.

Examples of data supporting solutions could include growing employment sectors within commuting distance, the number and location of the population trained for the jobs in the identified employment sectors, skills matching, or supportive service during training that increases successful completion. Other data may include the benefits from increased sewer and water capacity, allowing additional development, encouraging affordable housing within a commutable distance, new energy sources, or childcare enabling school or work attendance. Raising funds from any source requires building the case for need and success.

Suggestions to guide your data search:

American Community Survey is a good starting point. Many rural areas will need to rely on estimates of demographics and employment information, versus actual counts, due to the frequency of surveying. If you have identified a grant source, contact your program representative for direction on required and acceptable data sources and data age. Stats America has intuitive tools that may provide data you haven’t considered.

Look for data that shows the needs in the community that you’ve identified. This could be unemployment, median household income, age of housing stock, or school enrollment. Show historical trends, if possible, to highlight the change and causes of change. Here’s an example of a data source for broadband distress.

Compare your distress level with the distress level required by each agency or program for federal funds. Examples of distress levels among agencies include:

- Appalachian Regional Commission’s distressed index.

- Environmental Protection Administration with respect to environmental justice.

- The U.S. Department of Agriculture awards priority points to make applications addressing certain topics such as equity or originating from environmental justice communities. These points make applications more competitive.

- The Economic Development Administration requires a community demonstrate distress with median household income and unemployment levels.

Using the water line example, show the number of people served, the cost to the user, and the opportunity to develop additional land, creating more customers. Show how maintenance and operations will be paid for and who will do the jobs. Most grant applications will require this type of data, which is part of the design phase of a project like this.

Maps are powerful tools to show the locations of available land for water extension, the location of the most distressed areas, and the proximity to services, for example. Graphs help people see the changes without having to discern the impacts from the numeric values alone.

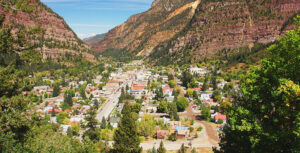

Photos that show the before and after of a neighborhood when a power plant closed, the historical view of the site, environmental features, road access, and anything that makes it clear about what is going on in your community and how you’d like to address it.

Testimony can be in the form of a quote, media reports, and other people’s words describing the situation and the benefits of addressing the needs you’ve identified. For example, if you are planning on providing training options or skills-matching services, include the story, with quotes, of the miner who has lost a job and does not have access to training, or an example of a power plant supply chain worker who found replacement work as a result of training.

Associated Resources

Listed below are examples of how other agencies and groups get started planning for transition.

These examples from the National Institute of Health show how data can be portrayed and used as support for a grant proposal.

This Prevention Institute document explains how to build effective coalitions, and how these coalitions can move a community toward their goals versus becoming stagnate in local dissention. The guide uses preventative health issues as an example.

The Grantsmanship Center outlines some basic guidance for using data in grant proposals.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency produced this document for community projects. It contains examples from a variety of applications and multiple resources for further study.

This is a discussion of using metrics with several examples from the Just Transition Fund.

Find Funding Options

Once you’ve identified the types of investments to make, consider pursuing funding through the Energy Communities IWG clearinghouse. The clearinghouse has funding options that are most useful for energy communities, as well as some general technical assistance and funding opportunities that can support economic development in your community.

The U.S. Economic Development Administration (EDA), Appalachian Regional Commission (ARC), and other federal agencies fund a wide range of investments, and there’s also specific funding available for infrastructure like broadband. There are also loans and tax credits available to businesses and communities. Engage with the private sector for cost share and other community benefits. Outside of the clearinghouse, there are additional sources of federal funding through Grants.gov.

The tough truth is that pre-application costs and cost share, or matching funds, can be prohibitive for many. Cost share is generally required to be secured or committed prior to applying. Pre-application costs, such as engineering and environmental reviews, are also required for most infrastructure projects and are not reimbursable. Loan programs can have very high minimum award levels with required matches, eliminating this option for many.

The good news is some programs have flexibility to decrease the cost share based on level of distress or specific funding. An example is the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Environmental Justice Screening Tool. Other programs give priority points for energy communities. The definition of energy communities varies by program. For the Inflation Reduction Act, the source of the most funds directly for energy communities, the definitions can be found here. Contact the Energy Communities IWG Navigator for any questions about the clearinghouse information.

Look to your state, local, or regional community foundations and philanthropy. Federal funds from one program cannot be used to match federal dollars from another program, with few exceptions. State, local, and private/philanthropic funds can be used as match, as can some in-kind contributions. The details of the requirements of each program should be discussed with the funding opportunity point of contact on the funding announcement.

Associated Resources

Listed below are suggestions for sources of nonfederal funding.

This is a resource showing community foundations nationwide from the Council on Foundations. Community foundations may also be able to direct applicants to other sources of philanthropic funds.

This is an example of state-level directory. While all the functionality isn’t available for nonmembers of the Council, a list of foundations is available with links to each foundation’s websites. This type of list exists for most states.

There are multiple websites of grant makers that have subject matter and deadline search functions. Most of these require a paid subscription. This website is an example of a website that offers training and other ways to find grants for a fee.

The Just Transition Fund offers financial assistance to groups that advance their mission and those located in areas supported by each of their programs. Grants are competitive and for the purpose of providing funds to match federal grants, attain broadband, and assist in grant writing. Technical assistance for planning and applications is also available.

Prepare Your Application

Many communities identify this step as being the most challenging. You’ve formulated your ideas and strategy, built a team, and found prospective funding. Now it’s time to navigate the federal grant applications.

The first step is making sure you have signed up for the federal grant system at SAM.gov. Grant applications are only accepted digitally through this system. (There are rare cases, however, when paper applications are accepted.) This system is not entirely intuitive to use, so patience is required. View the tutorials and find others who have used it. The technical assistance phone number for this site is very responsive, so use it.

Spend some time learning how to write a successful grant application. Look at successful applications. You may want to contact communities who have been successful receiving federal funds for similar projects to hear their experiences and lessons learned. Agencies publish their awards. Here are the recent U.S. Economic Development Administration awards, for instance.

Step 7 has several links that walk through every step, from signing up on the federal system, to collaborating with others, and eventually final submission. Don’t submit an application without speaking with your point of contact, who is listed in every notice of funding opportunity. Be sure to take advantage of agency-specific training. Ask your point of contact for guidance and to review your draft application. While no agency can assist in writing your grant, most can help you ensure the application is focused on the funding and is complete. They are here to help you succeed.

Associated Resources

Listed below are additional suggested resources regarding grant writing.

The Just Transition Fund offers technical assistance for grant applications in progress.

The Energy Communities IWG has an extensive list of guidance sorted by agency and by type of assistance. Much of this includes grant writing guidance and detailed information by agency.

This is a free federal resource that includes grant writing instruction, a searchable database of available federal funds, instructions for grantors and applicants, and forms.

This U.S. Department of Transportation checklist helps local governments prepare for the year ahead and chart a strategic pathway to take advantage of infrastructure investments by applying for competitive grant funding.

Implement the Project

Here is where the community can see what all the hard work has created. Whether it’s a bricks and mortar project, a planning project, or new staff, this is a step forward.

Implementation has its own set of bureaucratic requirements, from the request for proposals, to bidding, to awards. Many agencies will not allow expenditures until environmental requirements or other rules are met, so be sure there is a clear understanding of the sequence of events and the nature of the award. Some awards will reimburse expenses, others will distribute funds in increments, and still others are lump sum awards for specific actions.

There is training for this step, which is usually combined with project management and provided by the agency (Step 9), so don’t miss it. If the community has received other grants in the past, learn from that experience, and if it was successful, duplicate the process for this step.

Associated Resources

Listed below are additional suggest resources regarding project implementation.

The Energy Transition Playbook is written for managing complicated energy projects, but the process for implementation and management is the same for every project. The template for project tracking is useful for any implementation phase.

Manage Your Grant

This step is the second-most challenging (behind Step 7 – Applying) when it comes to receiving federal funds. Training in grant management is available from many agencies. Be sure to request it. Knowing the information to track before you spend or even receive funds will make it easier to complete the grant reporting for the term of the agreement. The glossary for this guide lists several grant management training programs by agency as examples.

A good time to evaluate is when the project has been completed. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) suggests this exercise in their publication Community Action Roadmap Step 6: Build Momentum for Change (EPA).

Ask yourself:

- What worked well?

- What could be improved?

- What are some ideas for addressing those challenges?

- Do you have existing partners who could help build success in these areas?

- Are there any new partnerships you could form to address any gaps?

- What are some next steps?

Associated Resources

Listed below are examples of how other agencies and groups get started planning for transition.

Grants.gov is the comprehensive source for everything from application to management, including forms. The site has contacts for assistance using the management tools and requirements specific to an agency.

Much of this grant management training module is applicable across federal agencies, although some is specific to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

Again, much of this U.S. Economic Development Administration training is applicable across agencies. This training includes managing planning, non-construction, and construction funding.

Share Success Stories

Success generates further success. Federal funds are directed at specific projects and outcomes and the intent of publishing federal funding opportunities is to help achieve those outcomes, with federal money. If you’ve been successful receiving federal, state, or philanthropic funds, or any combination, your community is inspiration for others to seek funds.

Get the word out about exciting new investments taking place in your community. Training and job placement successes are good opportunities to recognize the role that labor plays in a community and the companies that now employ newly trained people.

One strategy is to invite volunteers, elected officials, and reporters to participate in announcements and ribbon-cuttings. Demonstrate your successes and appreciation. Advertise why you’ve been successful – great local workforce, welcoming community, streamlined governmental regulations, available land, infrastructure, affordability, etc. Show what you have, sell it, and share it.

Using more suggestions from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s guidance, celebrate accomplishments with these ideas:

Using more suggestions from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s guidance, celebrate accomplishments with these ideas:

Thank you to all the organizations that contributed to the Energy Communities IWG Getting Started Guide. We appreciate your partnership in our efforts to revitalize America’s energy communities.

)

or https:// means you’ve safely connected to

the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official,

secure websites.

)

or https:// means you’ve safely connected to

the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official,

secure websites.